Microbes, human beings, and the many systems we inhabit, from farms to factories and hospitals to high schools, are all connected. Working in natural environments, research labs, and local communities, Rachel Whitaker has been studying the fascinating dynamics of microbial populations and their complex connections with biological systems for nearly two decades.

Whitaker, a member of the University of Illinois microbiology faculty since 2004, was recently appointed the Harry E. Preble Professor in the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences. The professorship was created to recognize accomplished faculty in the natural and mathematical sciences who make substantial contributions to diversity, equity, and inclusion in the academy and society.

“I am surprised and honored that I would be selected for this professorship,” Whitaker said. “I am also extremely excited to learn the Preble professorship recognizes the importance of integrating scientific inquiry with community engagement.”

Throughout her career, Whitaker has examined archaea (specifically, Sulfolobus) from the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia to the hot springs of Yellowstone National Park. Archaea are a domain of microorganisms discovered in 1977 by a team led by the late University of Illinois microbiology professor Carl Woese through ribosomal RNA analysis. Until then, scientists categorized life on earth into two main domains: eukarya (which includes plants and animals), and bacteria. Today, using tools available through genomics, scientists like Whitaker are studying how the archaea domain, the evolutionary sister of eukaryotes, evolves.

Studying evolution in natural systems pointed Whitaker toward the questions she has been exploring in recent years on virus-host interactions and how such interactions impact evolution.

“The really important thing to archaea and probably also to eukaryotes and bacteria and every living thing on earth, in terms of evolution, is their interactions with viruses and other kinds of mobile DNA,” Whitaker said.

Never has this been clearer to the world than now, after the COVID-19 pandemic has subsided following years of upending communities around the globe.

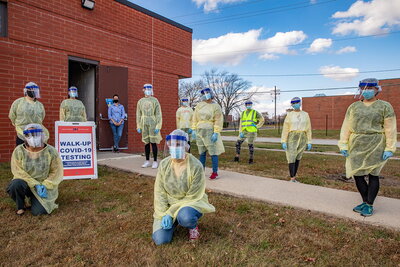

In early 2020 Whitaker reached back into her experience as a community organizer to assemble and work with an interdisciplinary team of faculty, students, clinicians, and community researchers to expand access to COVID-19 testing for communities without the access available on campus. In March of that year, they responded specifically to an outbreak in Rantoul, a community 15 miles north of campus and highly connected to Champaign-Urbana.

Although she has long been passionate about issues of education and equity, Whitaker’s career path to becoming a microbiology professor was not a direct one. After graduating college, she organized a community reading program for elementary school students in Portland, Oregon with AmeriCorps VISTA, the federal program whose mission is to alleviate poverty. She found it to be a rewarding experience, but when her time with the program ended, she was ready to explore a career in science. Her next step was working at a cancer immunology research lab, where she developed her love for research. But she wasn’t sure immunology was the right subject area for her. That led her to spending Thursday evenings in the public library reading science journals to find out what topics would pique her interest.

She found it while reading an article about Carl Woese and his contributions to microbiology, and specifically with archaea.

“My world was changed. At that moment I thought, how can I not study this?” she said.

After earning her PhD in microbiology and completing a postdoctoral research position at the University of California, Berkeley, she became a faculty member in the Department of Microbiology in the School of Molecular & Cellular Biology at the U of I, making her a colleague of Woese.

“I was really excited about the fact that by being in [the School of Molecular & Cellular Biology], and being in the microbiology department, it would be a way of bringing together molecular mechanisms with evolutionary principles. That’s at the essence of what makes archaea exciting to me. Their inner workings of the cell are like eukaryotes, but they’re free living, like single cells, like people think of bacteria. So how do those two things come together in terms of evolutionary processes? That was very exciting to me. And [UIUC] is the only place to do that,” she said.

Since she joined the Department of Microbiology and the Institute of Genomic Biology (named the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology after his death in 2012), Whitaker’s research has involved studying organisms such as archaea, bacteria in human diseases, and soil bacteria. As the theme leader for the Infection Genomics for One Health Theme at IGB, she and fellow scientists and students delve into the complex connections between human, animal, and environmental health.

She is also a co-leader of the Genomics and Eco-evolution in Multiscale Symbiosis (GEMS), created in 2020. GEMS is a Biology Integration Institute funded by the National Science Foundation. It spans several themes (symbiosis dynamics and discovery; rules of engagement, symbiosis as engines of rapid adaptation, integrated education, outreach, STEM equity and inclusion) and research projects involving over two dozen faculty and trainees at multiple institutions.

Since her experience after college, issues of education access, outreach, and equity remain close to Whitaker’s heart. For example, she has been involved for over eight years with a community-established collaboration between education and science at the U of I. Cena y Ciencias, a science outreach program in Spanish for dual language students in Champaign-Urbana public schools, was created by one of her Spanish-speaking students. Project Microbe, developed with professor Barbara Hug in the College of Education at the U of I, is an effort to weave the topic of microbes into the education system, especially at the high school and middle school level. The project offers free curriculum materials and organizes summer workshops for teachers. The COVID-19 pandemic has raised awareness of the importance of microbes in ecosystems, yet there is still a lot of education needed, Whitaker said.

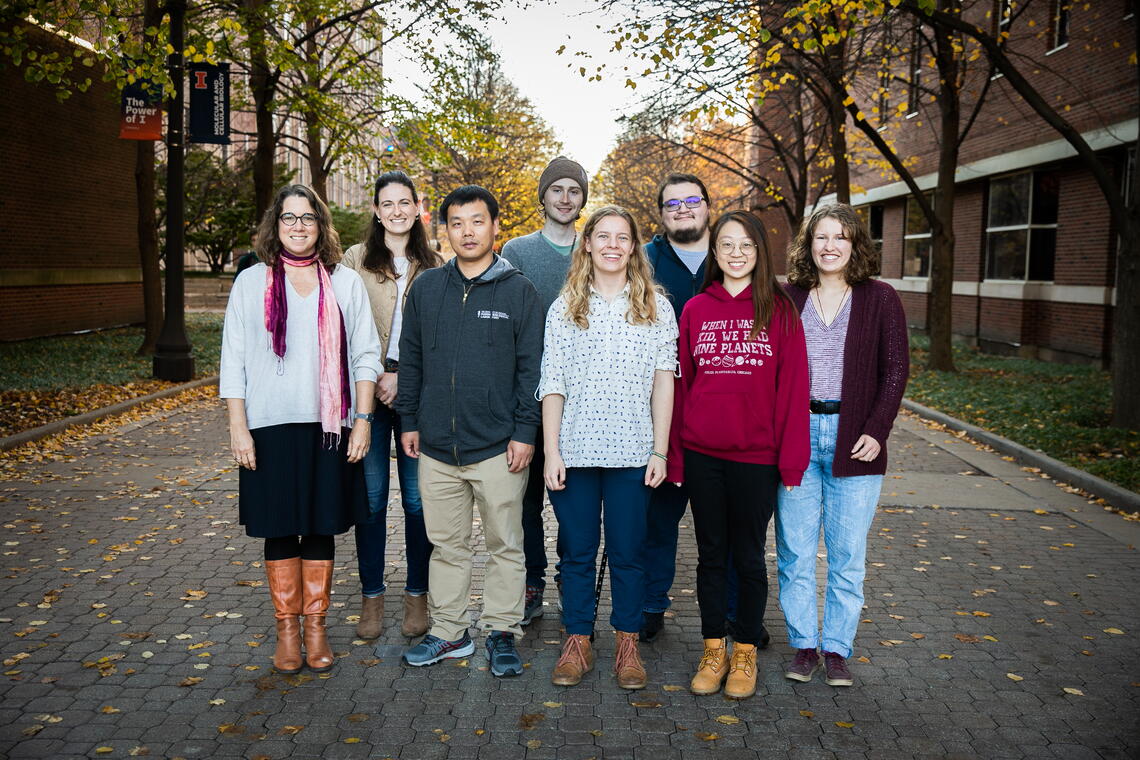

Whitaker is quick to point out that many of her lab’s activities (outreach and research alike) are driven by students.

“They have been very independent, determined, and focused students who are able to create their own projects,” she said. “That’s why we have lots of different systems where we’re studying similar fundamental processes. We’re studying evolution of virus-host interactions in microbes. But the number of systems we’re studying is increasing over time. Because people have come in with questions and we work together to figure out what system is the best,” she said.

What has emerged as an important and unifying theme as they’ve studied across these different systems, is that context matters; the context in which you’re evolving matters, she said.

Whitaker’s students have gone on to become postdocs in areas such as microbiome research, yeast genetics, virus-host interactions, and archaeal biology. Some work in forensics in national labs, while others have joined industry looking at, for example, using CRISPR to protect bacteria in industrial processes.

Reflecting on the COVID-19 outbreak in Rantoul, Whitaker said being involved in the response prompted her to think deeply about how issues such as access to healthcare and other institutional, structural, economic, and sociocultural factors that influence the evolution of infectious disease are all connected.

“Until we understand the real world and what defines interactions between people, and how they interact with and where and how and what, and how those things matter to their microbial ecosystems, including infectious diseases, we’re never going to be able to understand or control [viruses like the coronavirus or] the evolution of antibiotic resistance,” Whitaker said.

“We (university researchers) are studying everything from our academic context. And if we’re really going to understand the next pandemic, we’re going to need to look at it in the human context, and that human context has to include social and cultural aspects and all different types of economic status and aspects of human biology. The science we do needs to be done in a way that applies to the real world.”

Whitaker is very enthusiastic about the new community focus being suggested for the university’s strategic plan. The plan, called “Boldly Illinois: Strategic Plan 2030,” includes a goal to Make a Significant and Visible Societal Impact. When the core foundations of unabashed discovery combine with transformative learning and teaching, the outcomes are no longer measured simply in degrees or in citations,” the draft plan states. “They are seen in how the world is changed for the better through contact with the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The university lives up to its land-grant mission in many ways, and we will better organize, enrich, and value these contributions as we reach out to our local, regional, national, and global communities.”

“Truly interdisciplinary and engaged scholarship is necessary to create a resilient society that can respond quickly to global challenges,” Whitaker said.