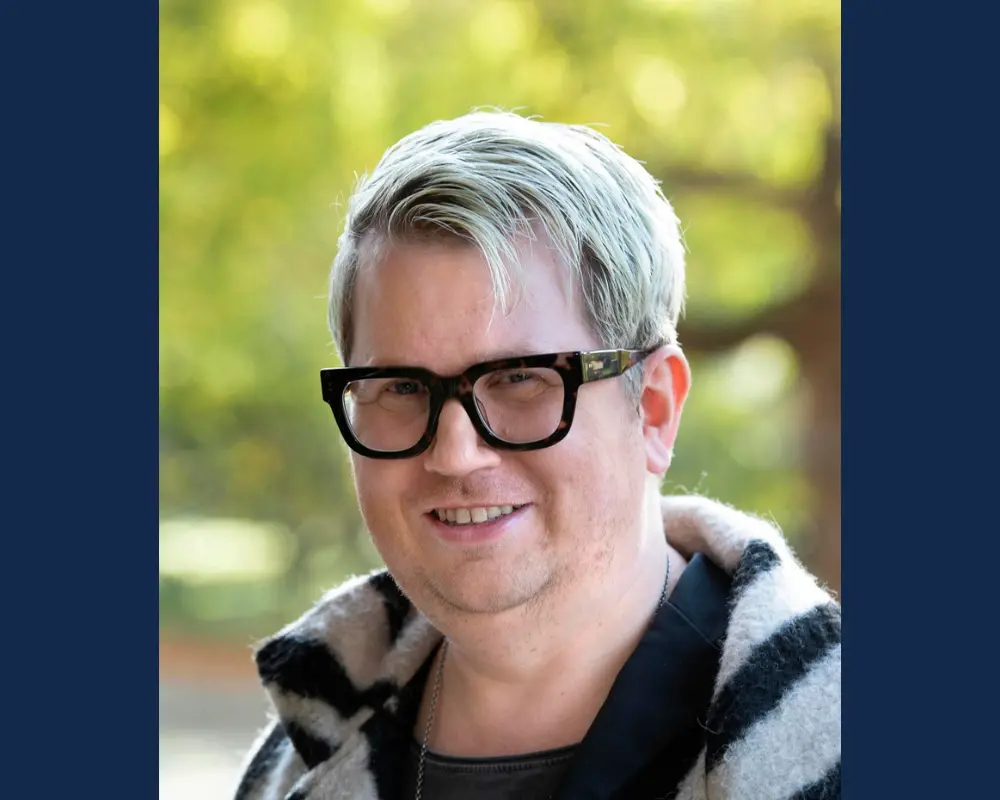

As an MCB major at the University of Illinois, Dr. Paul Donlin-Asp was an undergraduate researcher in Dr. Andrew Belmont’s lab and went on to pursue his PhD at Emory University. A former researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research’s Department of Synaptic Plasticity, he is now the Group leader (ESAT Fellow) at the Simons Initiative for the Developing Brain at Centre for Discovery Brain Science at the University of Edinburgh in the United Kingdom. He returned to campus this fall to deliver a lecture on “Resolving the dynamics of RNA and protein synthesis at the synapse” and met with students while here.

How did your time at Illinois shape your future experiences?

The access to undergraduate research definitely shaped me. I started out pre-med, like many in MCB, focusing early on with clinical volunteer experience. Then, in my sophomore year, I took a molecular genetics course and was introduced to epigenetics and chromatin organization. It was mind-blowing, and it pushed me to explore research. I started emailing labs, eventually joining Andy Belmont's lab, which changed my perspective. Instead of pursuing an MD-PhD, I realized research was my primary motivation.

Being a part of the Belmont lab was a pivotal experience. It allowed me to learn hands-on, and being in such an encouraging environment made the transition from student to researcher feel natural. This experience set the foundation for my future research career, shaping how I approached science and solidifying my passion for research.

Could you share any memorable aspects of working with Professor Andrew Belmont?

Working with the Belmont Lab was a lot of fun. I started with simple tasks such as PCR and visualizing gels, which built my lab skills and confidence. Over time, I gained more responsibilities, eventually leading to my research project. This gradual buildup of experience shaped how I approach mentoring students today, giving them small tasks to build confidence before diving into more significant challenges.

Dr. Belmont was always welcoming and encouraged me to attend lab meetings when I didn't have classes or other tasks. This made it easy for me to integrate into the lab community and understand the work going on around me. His supportive approach has stuck with me and influenced how I run my lab, fostering open communication and inclusivity.

What has been your favorite part of your journey so far?

Living abroad has been one of the most rewarding aspects of my journey. Sometimes, I forget how lucky I am to be in a beautiful place like Edinburgh, but then I walk past historic buildings and a castle on my way to work, and it hits me again. Growing up in the South of Chicago, this feels like an adventure.

Looking back, it reminds me of my time in Urbana-Champaign. At first, it felt like an enormous place, but by graduation, it seemed smaller, with familiar faces everywhere. I remember wanting to get out and see the world. I'm happy I've had the chance to do that, but there's nostalgia when I visit Illinois and see how things have changed.

What is your philosophy on building a supportive lab community?

I'm still learning how to build a supportive lab environment (Donlin Lab), especially now that I have my own lab. There's a difference between mentoring students in someone else's lab and being fully responsible for their experience in yours. Knowing how your interactions shape your time in the lab is essential. I start by clarifying that everyone should feel comfortable being who they are, which is rooted in my own experiences.

I also bring in people who are social, supportive, and open. Working in a lab can be challenging, so creating an environment where people can rely on each other is essential, especially when experiments fail or things get stressful. A lab is like a second home; everyone needs to feel like they belong and can have fun while working hard.

What advice would you offer to current MCB students at Illinois eager to explore research opportunities?

Ask around. Talk to recent graduates, PhD students, or professors about lab opportunities. It might feel daunting initially, but professors remember what being in your position is like. You don't need to know precisely what you want to do immediately. They aren't expecting you to have a clear vision, so focus on finding an environment where you can learn and grow.

Take advantage of any research programs the university offers. Sometimes, you won't know about opportunities until you ask. For example, I learned about the NIH postdoc program when an MD-PhD student who was my TA mentioned it. That conversation led to a life-changing experience.

What is the key piece of advice you’d offer for student mentorship?

Talk to your students about what they want. It's essential to guide them, but remember they're also looking for experiences that will help shape their careers. Conversations about their interests and plans can help them think more deeply about what they want to pursue.

Engage them in lab activities beyond their project, like journal clubs or discussions about papers. These are valuable opportunities for students to gain skills outside of the classroom and help them understand the broader context of scientific research.

Could you provide insights into your current research on RNA-binding proteins (RBPs)?

We're interested in understanding how neurons decide what proteins to make and when to make them, especially given the complexity of the human brain. Neurons can have thousands of connections, sometimes far from the cell body. To function correctly, they must produce proteins locally at these connections, where mRNA localization and translation come in.

My lab is focused on how RNA-binding proteins regulate this process. These proteins control all aspects of an mRNA's life, from transcription and splicing to translation and stability. We use a combination of imaging and proteomics to understand how neurons decide what proteins to produce at different locations.

What do you see as the future directions and potential implications of this research?

Moving forward, I want to move away from cultured neural systems and study this process in more complex circuits in the brain. While cell cultures are powerful tools, they only partially capture the complexity of the brain. Once we understand how neurons make decisions in these systems, we can explore how this process plays a role in learning and memory.

This research has enormous implications for neurodevelopmental disorders. Many genes associated with conditions like autism and intellectual disability are involved in local protein production. If we can understand how RNA-binding proteins regulate this process, we could develop strategies to increase protein production in cases where gene insufficiency leads to disease.

How have your service and outreach experiences contributed to your personal and professional development?

Service is a vital part of the scientific community. A lot of science relies on volunteer effort. I enjoy these roles because they allow me to give back and help shape how science is perceived and practiced.

Most recently, I became a reviewing editor for eLife, which was a meaningful opportunity because of the changes they've made to challenge traditional publishing models. It's been a great way to stay engaged with the community while learning more about the editorial process and improving my writing.