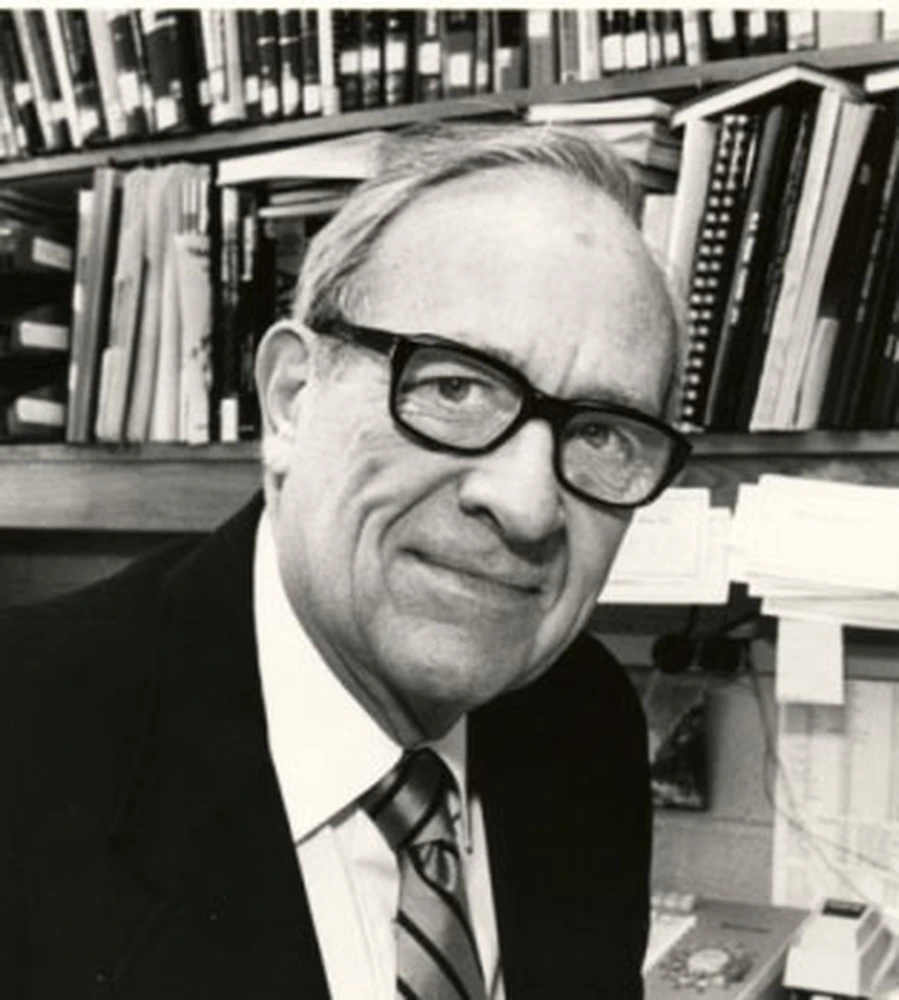

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. - Irwin C. Gunsalus, an internationally renowned biochemist and enzymologist who discovered several vitamins and made seminal contributions to the understanding of bacterial and human metabolism, died Oct. 25 at his home in Andalusia, Ala. He was 96.

The cause was congestive heart failure, said his daughter, C.K. Gunsalus, of Urbana, Ill.

In a career spanning nearly eight decades, Gunsalus, known as "Gunny," conducted research that led to many important discoveries on biological catalysis and regulation, the formation of essential metabolites, and mechanisms of chemical transformations and energy transfer critical to central metabolic reactions. His work drew upon many fields, including organic chemistry, physics and genetics.

In the early stages of his career as a nutritional biochemist, his investigation of bacterial growth factors and the chemistry of their actions led to the discovery of lipoic acid and pyridoxal phosphate (the active form of vitamin B-6) and showed how they each function in their co-enzyme forms to partner with enzymes during catalysis.

His work reinforced and contributed to a basic understanding of the roles of these universal co-factors in the central metabolism of microbes, plants and mammalian organisms. The discovery of lipoic acid was highlighted in The New York Times as one of the most important discoveries of 1953.

His subsequent research in the 1960s and '70s into the isolation, biochemical definition, and mechanistic understanding of bacterial cytochrome P-450 enzymes provided a foundation for understanding human liver metabolism and drug design.

Humans, animals and plants are now known to produce multiple P-450 proteins that help metabolize natural and man-made compounds and play critical roles in environmental adaptation and stress response.

Equally noteworthy was the genetic discovery of catabolic plasmids and their natural transmissibility among soil microbes, said Al Chakrabarty, a professor of biochemistry at the University of Illinois at Chicago who was a postdoctoral fellow with Gunsalus from 1965 to 1971. This work illustrated one mechanism by which microbes can acquire the ability to adapt in different nutritional environments.

Gunsalus conducted research and taught at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for 32 years, where he became a pioneer of cross-disciplinary collaborations. The pioneering biochemical and biophysical studies of Gunsalus with Hans Frauenfelder, Peter Debrunner and colleagues in the physics department at Illinois drove the understanding of biochemical processes of enzymes to a new level of mechanistic rigor.

Gunsalus was an exceptional role model for young scientists and colleagues, affecting the careers of thousands.

"He made me feel that I was joining a conspiracy of excellence," said Peter Wolynes, a theoretical biochemist and former U. of I. colleague now at the University of California at San Diego.

"Gunny was a charismatic leader of American science, being so obviously admirable that he provided an example that others felt inspired to follow," said Bruce Alberts, editor-in-chief of Science magazine and a former president of the National Academy of Sciences. "A born detective, he devoted his life to unraveling the chemical mysteries that make life possible. His pioneering, interdisciplinary approaches to deciphering the details of bacterial metabolism have helped to produce the vitality of modern biochemistry."

Starting in the 1950s, Gunsalus also developed an interest in French wines, visiting vineyards and wineries in France and becoming over the years an expert oenophile. Encountering difficulties in finding wines in the United States, he developed a relationship with a local liquor distributor to import wine directly.

Because of federal regulations at the time, each bottle was specially labeled as having been imported for him, an often-commented upon feature when friends and colleagues received bottles of wine as gifts.

Gunsalus held deep convictions about human rights, peace, and justice, and an ideal of global scientific cooperation. In 1967 he was one of four scientists who hand-delivered to President Lyndon B. Johnson a petition to halt the use of chemical and biological weapons in Vietnam. The petition was signed by 5,000 scientists, including 17 Nobel Prize-winners and 127 members of the National Academy of Sciences.

"Gunny was a great scientist and a great human being," said Frauenfelder, a member of the National Academy of Sciences and researcher at Los Alamos National Laboratory. "His science will live on through his collaborators and students, and particularly through his building of bridges between biology and physics. We will never forget his human side. Behind his sometimes stern and gruff exterior he hid a true human being."

"Gunny was more than a scientific mentor, collaborator and source of scientific inspiration," said Stephen Sligar, the I.C. Gunsalus Professor and head of the School of Molecular and Cellular Biology at Illinois. "He was a friend, who opened horizons revealing the truly international stage of science and education. One of his greatest products are the students and postdoctoral fellows who continue to carry forth his curiosity and demand for excellence."

A founding editor of Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, Gunsalus was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Academy of Microbiology and the National Academy of Sciences, chairing its biochemistry section from 1978-81. He received the Mead Johnson Award in Biochemistry, the Selman Waksman Award, and the William C. Rose Award in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. He was a Guggenheim Fellow and a Fogarty Scholar in Residence at the National Institutes of Health.

He held foreign membership in the French Académie des Sciences and honorary memberships in the Harvey Society of New York and the Japanese Biochemical Society.

Gunsalus served as president of the American Society of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology.

Born on the family homestead in Sully County in South Dakota on June 29, 1912, he spent his early years on the family farm prior to moving in 1919 to Brookings, S.D., to complete his primary and secondary schooling. He often talked about the emphasis his parents placed on education, noting that their schooling ended before college. His father was a self-taught master mechanic as well as farmer, and once machined a new part for Charles Lindbergh, who was forced to land in a field in the area. Gunsalus began his college education at South Dakota State College, before transferring to Cornell University in 1933. He earned his bachelor's (1935), master's (1937) and doctoral (1940) degrees in bacteriology at Cornell. He was a professor of bacteriology at Cornell from 1940-47. During World War II, he and his research team devoted most of their daytime hours to the study of disease risks and safe food concentrates for Britain.

Gunsalus was a professor at Indiana University from 1947-50 and at the University of Illinois from 1950-1982, and head of its biochemistrydepartment from 1955-1966. During these years he produced with Roger Stanier a five-volume treatise, "The Bacteria," which served as a foundational textbook to a generation of scientists.

After his then-mandatory retirement from Illinois at 65, he became an assistant secretary general of the United Nations, where he was the first director of the International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB) from 1986 to 1989, initiating scientific outreach programs to Third World peoples and overseeing the construction and establishment of research centers in Trieste, Italy, and in New Delhi. ICGEB is dedicated to international cooperation in developing and applying genetic engineering and biotechnology to pressing problems of development, and to strengthening the scientific and technological capabilities of developing countries in this field.

Following that term of service, he moved to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's National Health and Environmental Effects Laboratory, Gulf Ecology Division, as a senior scientist from 1993 to 2003, studying the microbiological bioremediation of coastal ecosystems.

He is survived by his sister, Anna Gunsalus Higgs, of St. Paul, Minn.; his children, Ann Gunsalus Miguel, Pasadena, Calif.; C.K. Gunsalus; Glen Gunsalus, Graton, Calif.; Kristin C. Gunsalus, New York City; Richard Gunsalus, Los Gatos, Calif.; Robert Gunsalus, Los Angeles; and seven grandchildren. Merle Lamont Gunsalus, of Brookings, S.D., his first wife, survives. His second wife, Carolyn Foust Gunsalus, died in 1970; his third wife, Dorothy Clark Gunsalus, died in 1981; and his son, Gene Gunsalus, died in 2006.