A research article, communicated jointly by Professor of Molecular and Integrative Physiology Milan Bagchi, and Professor of Comparative Biosciences Indrani Bagchi, has been published in the journal Science. In this paper, researchers at the NIH-funded Center of Research in Reproduction at the University of Illinois address an important unresolved issue in steroid hormone biology: the mechanism by which progesterone counteracts estrogen-induced uterine growth. The antiproliferative action of progesterone in the uterus is of high clinical significance since breakdown of this action underpins female infertility as well as estrogen-driven hyperplasia and endometrial cancer.

University researchers funded by the National Institutes of Health have identified a key step in the establishment of a pregnancy: how the hormone progesterone suppresses the growth of the uterus’s lining so that a fertilized egg can implant in the uterus.

This key step, the researchers discovered, occurs when a protein called Hand2 suppresses the chemical activity that stimulates growth of the uterine lining, also known as uterine epithelium.

At the start of each menstrual cycle, levels of the hormone estrogen begin to rise. Estrogen stimulates the cells in the uterine lining to increase in number, causing the epithelium to thicken. However, as the ovary releases an egg, levels of the hormone progesterone begin to rise. The elevated progesterone levels put the brakes on this estrogen-driven growth of the uterine epithelium. In this study, the researchers discovered that Hand2, previously found to increase in uterine cells with rising progesterone levels, is the switch that turns off estrogen’s stimulating effect on the epithelium.

The finding may contribute to an understanding of at least some forms of unexplained female infertility. The finding also has implications for understanding disorders in which uterine growth surges out of control, such as in endometrial cancer or endometriosis, a disease in which endometrial tissue attaches to inappropriate sites and grows outside the uterus.

“Progesterone-like medications are used to treat a wide variety of conditions, such as relieving the symptoms of menopause, as part of infertility treatments, and for preventing preterm birth,” said Louis DePaolo, Ph.D., head of the Reproductive Sciences Branch at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the NIH institute that funded the study. “Understanding how Hand2 exerts its effect on uterine growth may lead to the development of new medications and therapeutics that make progesterone treatment more effective and with fewer side effects, as well as provide important insights to the etiology of progesterone-resistant diseases such as endometriosis.”

First author Research Scientist Quanxi Li of the Department of Comparative Biosciences was joined on the research team by corresponding authors Professor of Molecular and Integrative Physiology Milan K. Bagchi and Professor of Comparative Biosciences Indrani Bagchi, and their Illinois colleagues Athilakshmi Kannan and Paul S. Cooke; Francesco J. DeMayo and John P. Lydon of Baylor College of Medicine; Hiroyuki Yamagishi of Keio University School of Medicine; and Deepak Srivastava of the University of California, San Francisco. Their findings appear in the Feb. 18 issue of Science.

The research was supported by the NICHD Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research (SCCPIR), a collaborative network of basic and clinical scientists, with the ultimate goal of improving reproductive health.

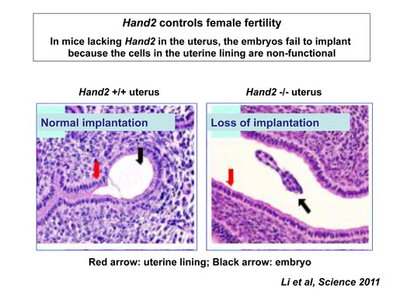

For the current study, the researchers developed a laboratory strain of mice in which the uterus fails to make Hand2.

The researchers found that, after exposure to progesterone, growth of uterine epithelium in mice with functioning genes for Hand2 halted, but continued unchecked in the mice without Hand2 genes.

They also discovered that, at the time of implantation, Hand2 was expressed in uterine cells that lie beneath the surface layer of epithelial cells. Through a series of experiments, the researchers determined that estrogen stimulates the production of growth factors, which cause cells in the epithelial layer to multiply and grow. When progesterone is produced, it spurs the expression of Hand2, which stops the production of growth factors. The uterine epithelial cells stop multiplying, and then mature so that they can attach to the embryo to begin the implantation process.

“This information helps us understand how an interplay of hormones prepares the uterus to host and support the embryo as it grows,” said Dr. Milan Bagchi. “Our next priority will be to examine whether Hand2 plays a critical role in the human uterus as well.”

Adapted from a NIH press release.