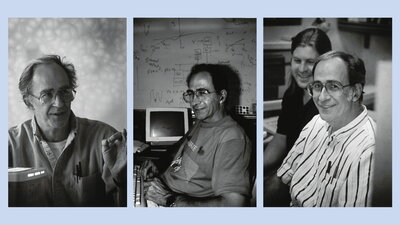

URBANA — Longtime Urbana resident Eric Jakobsson is being remembered as a devoted husband and father, a brilliant scientist and mentor, a political bridge-builder and all-around nice guy.

The 82-year-old died in his stately Main Street home on Thursday, Oct. 28, 2021, from cancer. He leaves behind his wife of 58 years and seven of their eight children.

“He was such a wonderful father, a friend to so many people, an advocate for so many good causes for years and a wonderful husband,” said his wife, Naomi, who called her spouse “a real Renaissance man.”

“The science, community service, the family, acting, so many things. He wrote poems to me on birthdays, our anniversary, Valentine’s Day, Mother’s Day,” she said of the man who supported her in all aspects of their life, including her active political life as Champaign County recorder of deeds and an Illinois state legislator for 12 years.

The family is planning a memorial service for some time in the future.

“Eric was a very special individual. He had a far-ranging intellect, a probing mind,” said Gene Robinson, director of the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology at the University of Illinois with which Mr. Jakobsson was affiliated. With advanced degrees in engineering and physics, Mr. Jakobsson moved with his wife moved from Ohio to Urbana in 1971 where he began his 50-year association with the UI.

His list of educational and career accomplishments is long and rich — professor of biochemistry, molecular and integrative physiology, biophysics and computational biology, bioengineering, neuroscience — and praise from his colleagues effusive.

Although he had “emeritus” in front of his many professor titles, Mr. Jakobsson continued to work as he dealt with his health challenges. As recently as the spring semester, he was teaching a course on the history of the universe to honors students at the UI, remotely due to COVID-19.

“He formally retired, but you would not be able to tell the difference in what he did before and after,” Robinson said.

“His main area of research was in studying microscopic cells, especially nerve cells called ion channels that allow chemicals to go in and out of nerve cells,” said Robinson, who explained that understanding ion channels is fundamental to understanding the nervous system and how the brain works.

Robinson collaborated with Mr. Jakobsson researching how some genes that influence behavior in honeybees could have similar influences in mammals, including humans.

“His lab developed really powerful new computational tools to test the idea and indeed we did find evidence for evolutionary conservation,” Robinson said. “In English, that means the genes that have a function in honeybees are having a similar function in mammals.

“He saw excitement and potential in everything and everyone and gave great encouragement and was just a delight,” Robinson added. “He was incredibly fun. He was interested in so many things and he could make connections fast between disparate areas of study.”

Claudio Grosman, head of the department of molecular and integrative physiology where Mr. Jakobsson worked, agreed, saying he was part of the reason Grosman came to the UI 20 years ago.

“I first met him when I was interviewing as a job candidate. His warmth brought me from the East Coast to the West,” said Grosman, a native of Argentina, who said Mr. Jakobsson treated him as a peer from the get-go.

“He was the opposite of aloof,” said Grosman, who also collaborated with Mr. Jakobsson on ion channels. “I remember being very skeptical and told him, ‘You must be wrong,’ and he ended up being right. He showed the world that brain ion channels that we thought for decades were exclusive to animals, (were) in the simplest organisms, which are bacteria. Eric taught the world a lesson in humbleness.” Grosman said even in brief meetings, Mr. Jakobsson quenched his thirst for ”intellectual interaction.”

“I would bounce my ideas against him to see if they stick or fall. I recognize that in some of my papers, my work has been heavily influenced by him,” said Grosman, adding it might have been only one or two words from Mr. Jakobsson but was enough to help him shape his own insight.

Urbana Mayor Diane Marlin used her friend and fellow moderate Democrat for the same function.

She was elected as alderman in 2009, a year before Mr. Jakobsson was appointed to the city council.

He later ran for election to Ward 2, which covers much of the area west of downtown, and served until he resigned in June 2020 at age 81 to devote more time to teaching.

Marlin got to know him well in that decade.

“What drew me to him and what struck you all the time was that he was so principled,” she said. “He always reminded you of what was right and just. He had a true north.

“He stood up for the underdog. He had a great sense of humor. He was just a well-rounded person. He was compassionate and really cared about the community,” she added, saying his votes were cast “in the best interest of the community.”

“Sometimes that involved compromise. He had a very good political sense too, and a sense of people and how to work with people,” Marlin said. “No matter what your opinion was about something, he could have a productive, lively, passionate discussion. People felt like they had been listened to and heard. That’s an art we are not seeing as much anymore anywhere.”

Former City Clerk Phyllis Clark observed that Mr. Jakobsson always studied the materials she prepared in advance of meetings and was ready with his questions and thoughts.

Besides serving on the city council, he was also a representative to the public arts and culture commission, the Urbana Free Library board and the traffic commission to name a few.

“He always had a little joke to break the ice and bring things back around. He was a great guy and he’s going to be missed,” said Clark, who had one little bone to pick with Mr. Jakobsson.

A self-described “stickler for the right thing to do,” Clark disapproved of him wearing a ball cap at meetings because it made it difficult to see his face. Declaring that his hat “defined” him, Mr. Jakobsson declined her request to remove it during meetings. That is, until Clark got the upper hand.

“I said, ‘Eric, when I finish taking this roll call and if you still have that hat on, I’m going to get up, come over there and take it off.’ He left that hat on until I got to the last council member. Then when I called the last name, he took the hat off and put it in front of him at his council space. And he did that the entire time until I retired,” said Clark, who left her post in 2017 after 24 years of service.

Coming back for a meeting after she retired, he greeted her with his hat on, devilishly declaring “I can wear my hat now.”

Marlin said her friend and colleague was devoted to his wife, with whom he was active in politics, the McKinley Presbyterian Church, and many community organizations.

“At the center were Eric and Naomi. It was two for one. They always called each other ‘my girlfriend’ and ‘my boyfriend’ to the very end,” she said, adding he was very proud of his eight children and 15 grandchildren. “He loved his family dearly, and they opened their house to the world.”

Eldest child Beverly Adamczyk said her dad loved doing things outside with the whole family. One of two biological children of the Jakobssons, Adamczyk said her parents fostered children for many years and adopted six more. There is a span of 12 years from oldest to youngest, some of whom are very close in age. “They wanted a big family and they thought there were already children in the world who needed homes and they decided to adopt,” she said. “He loved family vacations when we were kids. We went camping.

“During the week, he worked hard, and I have memories of him taking me to the computer lab and running punch cards with him. He invited us into his world. I liked to play with his slide rule,” she said of the precursor to a calculator. “He took time with the family. When I was older and there were younger children, family trips might be part of a conference. He would turn it into family time,” she said.

The Jakobssons lost son Garret in 2013 to a neurodegenerative disease. He was 46.

Grosman said he believed that motivated his colleague’s shift into research on lithium, on which he wrote several papers toward the end of his career.

“It seems to me that this place, Champaign-Urbana, which is so hard to understand, won’t be the same without him,” Grosman said.