The recent rise in cases of a drug-resistant fungus called Candida auris has prompted hospitals and nursing homes to be on alert and sparked concern among scientists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which deemed it an “urgent microbial resistance threat.” The emergence of an infectious superbug is not a new occurrence though; it is the latest in a growing number of pathogens threatening our communities and our health. This war between microbes and antibiotics has been waging for a long time.

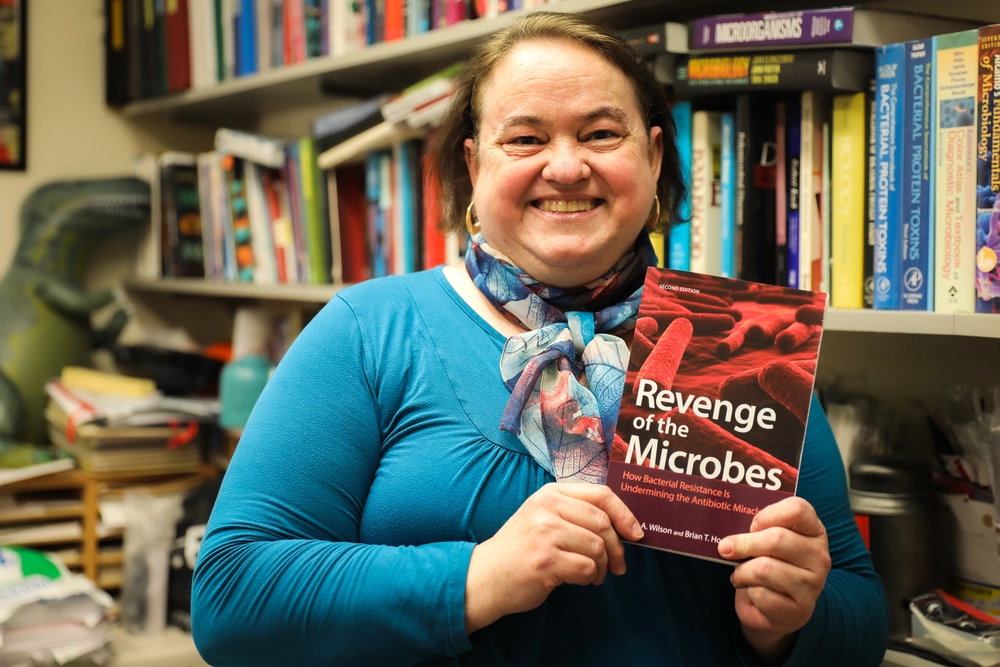

In Revenge of the Microbes: How Bacterial Resistance is Undermining the Antibiotic Miracle, University of Illinois professor of microbiology Brenda Wilson and co-author Brian Ho provide timely and in-depth information and analysis of antibiotic resistance and the emergence of superbugs. In accessible language, the authors offer a history of antibiotics and their mechanisms of targeting and killing microbes and how microbes develop resistance to antibiotics. Wilson and Ho analyze our current predicament through a holistic lens that goes beyond pure microbiology to encapsulate how the antibiotic-microbe arms race involves us all.

What exactly is this antibiotic-microbe arms race?

“It’s the struggle we have with bacteria developing antibiotic resistance repeatedly,” Wilson explained. “The mutants that survive antibiotic application develop resistance to the antibiotic and pass it on, so we continue having to find other types of antibiotics against which the microbes have not yet developed resistance.”

Since microbes gain resistance based on recognizing the structure of the antibiotic and circumventing their effects through pumping them out of the cell or by producing enzymes to render them ineffective, any antibiotics with a similar structure to that antibiotic to which it’s already resistant would also have little to no effect on the microbe. This effectively rules out class after class of antibiotics as treatments, causing researchers to continuously search for new antibiotics with vastly different structures.

“Many good and safe drugs (thus) are no longer useful, so we start having to move on to more toxic drugs until microbes gain resistance to those, too. We will eventually have to keep moving on to more toxic drugs, until it becomes a question of whether the drug does more harm to us than good,” Wilson said.

Exacerbating the situation is the ability of microbes to gain multidrug resistance, or MDR. Wilson’s lab is dedicated to studying host-microbe interactions. One of the bacterial strains they have studied has devastated flocks of pheasants. Upon sequencing its genome, their lab discovered the strain possessed at least 38 antibiotic-resistant genes, with only one antibiotic having a limited effect on the bacteria.

In the book, the authors explained that pathogens are either naturally resistant or gain resistance through uptake of resistance genes. This does not bode well for human beings. Pathogens that gain multidrug resistance could become untreatable by most forms of antibiotics, resulting in us going back to the pre-antibiotic times, that is, before the early 1900s when there were no antibiotics available.

How did this happen?

While there are multiple factors that have led up to the current state of events, Wilson and Ho highlight the overuse and misuse of antibiotics by farmers and physicians, and the fact that pharmaceutical companies have few incentives to produce new antibiotics.

“We have this problem of antibiotics dumping on crops and animals. Antibiotics are very stable, and through animal feces can end up in the soil and water, causing them to spread. Any time you introduce this into a system with a lot of microbes, they will gain resistance. We end up making the whole ecosystem change and this perturbs everything we do.” Wilson adds that over-prescription of antibiotics by doctors can likewise contribute to the spread of resistance.

As for pharmaceutical companies, they have little incentive to create new antibiotics, she said. The rate at which microbes take up resistance genes renders antibiotics useless fast, making the return on the oft-large investment not worthwhile, amongst other reasons.

Rising to the challenge

Wilson, whose PhD research was in antibiotic biosynthesis in microbes, said it is pertinent now more than ever to ensure that the public understands the breadth and severity of this problem.

“I hope that students are inspired to participate,” she said. “I hope (students) realize how grave the situation is and (they) rise to the challenge and understand that they need to help. Most importantly, I want to lead them to make informed decisions; not to dictate them to do things but to give them the knowledge to empower themselves.”

For Wilson, this book is a labor of love in two ways. This is a “legacy” book, with Wilson carrying the torch for her close friend and colleague, the late Abigail Salyers, University of Illinois Arends Professor Emerita of Microbiology. Salyers wrote the first edition, Revenge of the Microbes: How Bacterial Resistance is Undermining the Antibiotic Miracle, alongside associate professor of clinical microbiology Dixie Whitt in 2005. The second edition was co-written with Wilson’s son, a faculty member at the University College London who studies gene exchange mechanisms in bacteria.