Dr. Lori Raetzman is a professor of molecular and integrative physiology whose research program focuses on understanding the role of cell-cell signaling during pituitary development. She is also the Associate Director for the School of MCB PhD Programs. She spoke with graduate student Manasi Inamdar for a feature in the 2024 Molecular & Integrative Physiology newsletter.

Looking back to when you first became interested in science, was there a defining moment or mentor who inspired you?

The person that first got me into science was my dad. He was really good with his hands, and we would always build contraptions. If we needed to pick up after the dog, he made a pooper scooper. He also created a sprinkler for watering the garden that covered the whole space. He loved creating solutions for problems. Behind our house, there was a drainage ditch with tons of wildlife, and he made things so I could catch fish. He worked in a factory and was not a scientist or engineer, but his interest in creating and solving problems sparked my interest in the natural world. My biology career was definitely influenced by my summer research internship at the Mayo Clinic. I attended a small liberal arts school, where I had biology classes but no labs. I loved biology but didn’t consider it as a career until that summer research experience changed everything; it was exactly what I wanted to do.

How did your doctoral and post-doctoral experiences shape your research career?

When I went to do my PhD, I was very interested in Alzheimer's disease. I looked into neuroscience programs with a strong Alzheimer's focus, and I rotated through several labs in that area. Although the atmosphere of the university was fantastic, the atmosphere in those labs was highly competitive because that topic was very popular. People were looking for drugs, and there was potential for patents. I realized that I loved the science, but not the scrappy fight of working on something that someone could scoop you on the next day. I recognized this during my rotations, which was good. I then ended up picking a lab in another strength of the department, which was developmental biology, and I ended up in a developmental neuroscience lab. I loved the lab and the topic, and I'm working in development to this day because of that experience.

My postdoc mentor, Dr. Sally Camper, is probably the most influential person in my entire career. I loved working with her and my project, but she has also been the biggest sponsor of my career. I've given talks because she specifically declined the talk and told them I should give it instead. I've gotten so many opportunities because she's opened doors for me long after I was in her lab. I would say to anyone, if you can, you need mentors in your life, no matter what your stage. Finding someone who will really stick their neck out for you is transformative.

What inspired you to pursue a career in academia and establish your research lab at Illinois?

I loved my PhD and knew I was going to do a postdoc because I loved my science. But while I was in that postdoc, I wasn't quite sure what was next. Some of it I think was self-confidence. I didn't know if I was good enough to be a faculty. I was thinking broadly, but again, my postdoc mentor, without doing anything formally, would just make sure to highlight opportunities like internal grant applications and encourage me to write them. Those little nudges gave me the confidence that I was capable and that I was doing well, without directly telling me I should be faculty. She let me build confidence. Having a mentor who knows how to do that is pretty special. Eventually, I gained the confidence to apply for jobs, thinking, “Yes, this is what I should be doing. I am good enough to do this and I can.”

I interviewed at a bunch of places, liked different aspects, and really loved how collaborative things were here at UIUC. Also, one of my best friends was a professor here and having a good friend here was a big pull for me. I knew I’d have a community already with her, and if she liked it here, that meant there was a good community here. And number two on the list of selling points was Ann Nardulli, a professor in our department. Having a strong female mentor is really important and she was the next big influence in my life. She celebrated success with me and helped me through the difficult times, providing chocolate for both occasions.

Could you describe your current research area? What are the main questions or challenges that motivate your work?

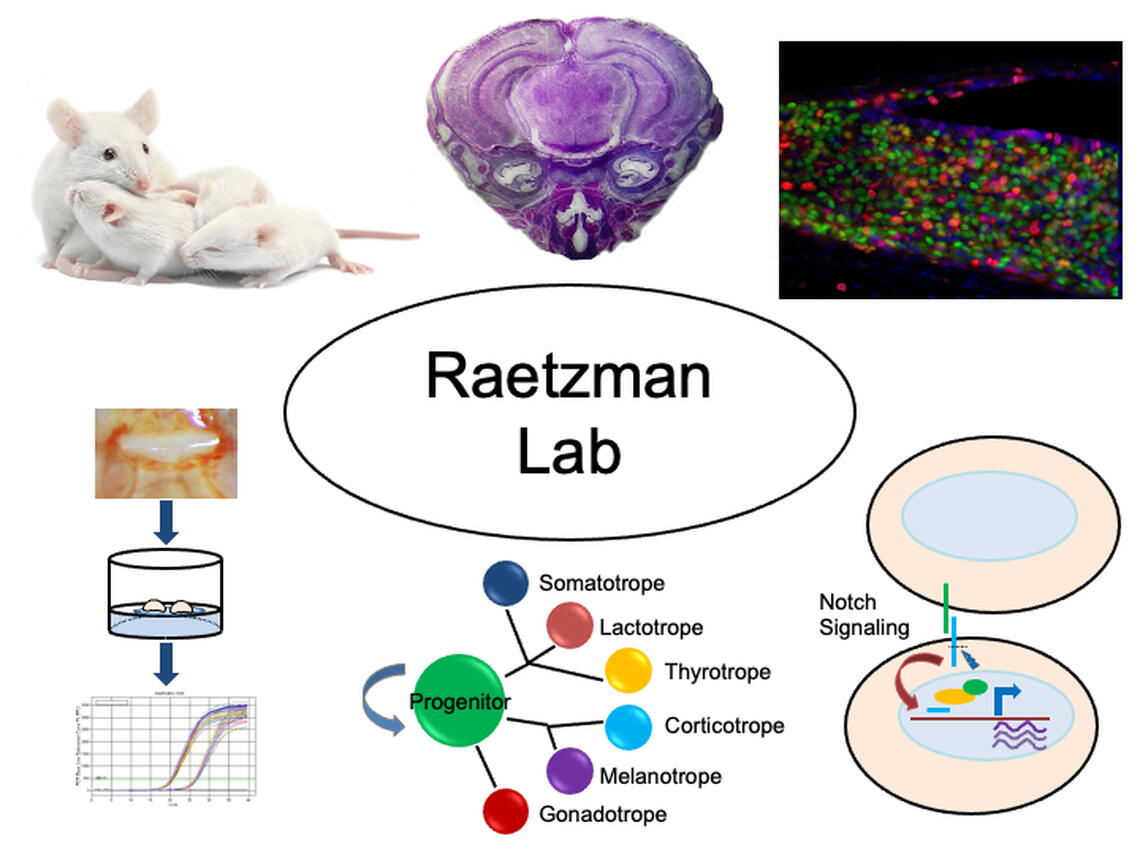

The main focus of my lab is understanding the causes of hypopituitarism, a disease of pituitary development. About one in four thousand births result in developmental midline defects, including hypopituitarism. Sometimes it's just hypopituitarism, but other times it can be related to conditions like holoprosencephaly or other problems with the brain and the midline. This disease intrigues me because it involves both the brain and the pituitary. Interestingly, only 20% of cases have an identified molecular cause, leaving 80% undetermined. We believe it's likely a mix of genetics and environment—either one alone or a combination—that can adversely affect development. This has allowed me to explore environmental factors like endocrine-disrupting chemicals, as well as genes known to influence pituitary development, to see how they might work independently or interact in terms of causing pituitary formation issues and hypopituitarism if they aren't correct.

I'm particularly excited about a group grant project we're currently working on. We're investigating mouse mutants with malformed pituitaries based on MRI sections of knockout mice. This effort is part of the International Mouse Phenotyping Project, which aims to characterize all generated knockout mice. After scanning a large number of these mice, we selected those with pituitary defects that were previously not linked to genes critical for pituitary development. Our focus is on understanding how the loss of these genes impacts the midline. Additionally, we're collaborating with a network of clinicians in Argentina who are identifying mutations in these same genes. It's been really fun. This dual approach—combining clinical insights with research—has been incredibly rewarding. I'm hoping the rest of my lab, studying environmental factors affecting pituitary development and function, will weave into this project as well.

As the Associate Director of the School of MCB PhD programs, how has this leadership position shaped your views on education and research? What goals or initiatives are you most passionate about?

I was encouraged to take on this role as I've had a long-standing interest in graduate student mentoring. I was the chair of the Endocrine Society Trainee and Career Development Core Committee and am currently the chair of the FASEB Training and Career Opportunities Subcommittee. I've enjoyed contributing to these conversations on mentoring and career development and it's been great that I've been able to now bring some of the knowledge here. I am most excited about implementing holistic admissions because I believe it's essential to recruit a strong, diverse student body. Relying solely on metrics like GPA and GRE scores is insufficient, as these do not strongly correlate with student success. Factors such as resilience are much more predictive of thriving in graduate school.

The other thing I feel very strongly about is career opportunities. MCB is hiring a career coordinator for undergraduates and graduate students. This will be the first step in having a person looking specifically at non-academic careers and will provide information about industry and government and help make connections. The next thing I want to do is create a website that lists all campus opportunities for enrichment such as information about the teaching certificate, Illinois business consulting, and outreach programs. I want to consolidate these resources so that when people are looking for career exploration or enrichment, they don’t have to rely on a whisper network. Instead, there will be a central place where students who have had positive experiences can share what they did and what they gained from it. This will allow for contributions from anyone who has participated in these activities.

I have also been focusing on improving transparency. Students prefer to know what’s happening rather than having to guess. To address this, we created an MCB graduate student handbook, which did not previously exist. This handbook consolidates essential information into one accessible location and helps us avoid inconsistencies. My goal is to hold myself and the program accountable while making it easier for students to find crucial information. I'm not sure how long I will continue in this role, but if I can make a difference, then it will be worthwhile.

What advice would you give to young scientists and trainees aiming to build successful, impactful careers?

You need to work on something you feel passionate about, but it doesn't have to be in grad school. Grad school is about learning how to do science and building a network. You don't have to know exactly what you want to do with your life halfway through grad school. You should continue exploring and figuring out yourself to know what motivates you. By the time you're a postdoc, if that's the path you choose, you need to be working on something you love because that is going to be your day in and day out. It's hard to go to work if you don't love your research. So, determine what you enjoy, how you like structuring your day, and find a job that allows you to do what you love in the way you love doing it.

A mentor doesn't have to be someone you talk to every week; it could be someone you connect with occasionally. You can use LinkedIn to find people in industry for informational interviews, and you might find someone willing to meet once a month or even once a year to discuss their insights. Cultivating relationships with mentors and trusted individuals is essential; even as a senior faculty member, I continue to rely on my mentors. Start early and don't view asking for opinions as a weakness. It's a way to clarify your goals by vocalizing them and hearing someone else's response. So, seek out mentors.

What hobbies or activities do you enjoy outside of the lab to help you unwind?

The biggest thing I love to do is cook. I have a garden; I go to the farmers market every week. I spend a lot of time thinking about food. I like going to fancy restaurants in Chicago; all things food. And I love spending time with my cats and my husband. That's probably my two biggest hobbies: cooking and cats.

Many of your students and trainees speak highly of your mentorship. What do you find most fulfilling about mentoring, and how do you help each person reach their potential?

What I find most fulfilling about mentoring is watching students have their "aha" moments. They may come in feeling a bit panicked about something, and then after we walk through it together, they gain clarity. The next time they come, it's rewarding to see them build on what I've said. I feel that I'm shaping their trajectory and helping them take full advantage of opportunities. It's not just about providing a lab space; it's about guiding them on how to utilize it effectively. This includes knowing deadlines for abstracts and meetings to ensure everyone gets an opportunity. I love helping in that regard. In terms of helping people reach their potential, I try helping them in figuring out what they like. Much of our mentoring conversations revolve around data, discussing what the results look like and what steps to take next.

It’s essential to be intentional about also asking, “What are you thinking about for the future?” Even if it’s just once a year at the annual review, I’ll suggest, “You haven’t done a teaching activity yet; perhaps you should try this,” or “What do you think about outreach opportunities?” I encourage them to think about their progress. If a student isn’t advancing in their research, it’s crucial to understand why—rather than simply urging them to "do more." There may be underlying reasons for their stagnation. They could be struggling with certain concepts or not working efficiently. These issues can often be addressed through conversation and mentorship, but without that dialogue, we may never uncover the root of the problem.

Reflecting on your recent promotion to full professor, what are you most excited about in this next stage of your career?

Taking this leadership role within the school goes hand in hand with that. I was looking forward to being in a position where I could assume leadership roles. While I have been active in my scientific societies, I am excited about the opportunity to do some of that here, too. I have greatly enjoyed mentoring students, and I would enjoy the chance to mentor junior faculty in a more meaningful way. While I serve on faculty mentoring committees, I often feel that my contributions are limited; offering a few words here and there doesn't feel as impactful. In contrast, hiring someone and having regular meetings with them would enable me to understand their research better and assist them with grant writing or planning their next steps. That level of engagement would be incredibly rewarding.