In new research, University of Illinois scientists have challenged previously held scientific ideas about loop-C’s functional role within ligand-gated ion channels, deepening biologists’ understanding of the complex neurotransmission process.

Their study, “Disentangling the mechanistic role of loop-C capping in Cys-loop receptor activation,” was published in Nature Communications.

Claudio Grosman, professor and head of the Department of Molecular & Integrative Physiology, and research scientist Dr. Gisela Cymes work on membrane receptors that, upon binding neurotransmitters to their extracellular side, open ion-permeable pores in the plasma membrane.

“In this way, neurotransmitter binding elicits a transient change in the electrical properties of a cell, such as the membrane potential, and/or allows the influx of calcium ions into the cytosol, both of which can trigger further signaling events. We are interested in understanding how the structure of these neurotransmitter-gated ion channels gives rise to their function as they ‘jump’ between different conformations,” Cymes said.

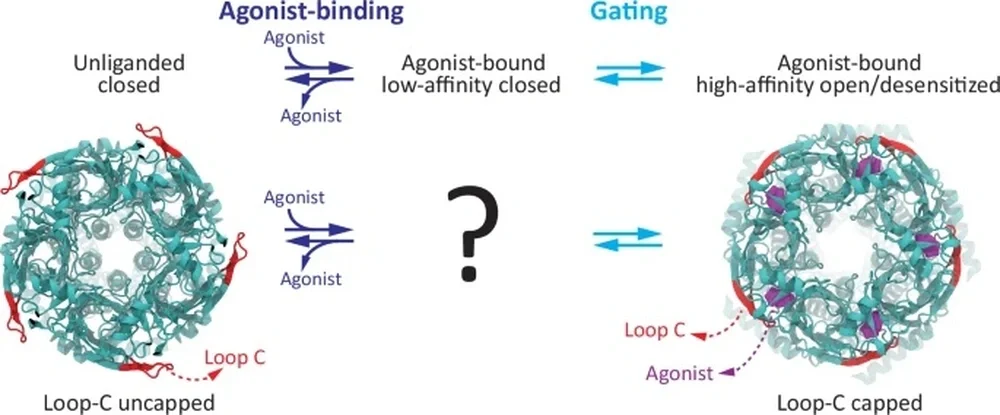

A ligand-gated ion channel (LGIC), lying on a neuron’s dendrite, has parts that are encased by, lie within, and extend beyond the cell membrane. Loop-C is found in the latter: an ideal site for stray ligands. Like a microscopic Venus flytrap, loop-C closes around — or “caps” — any ligand that makes contact.

“Then, a domino effect would open up the LGIC,” Grosman said. ‘How can a ligand binding in the extracellular domain open up a port in the transmembrane domain?’”

In other words, what does the lock mechanism look like? After the loop-C lock receives the ligand key on the exterior, what cascading pin releases occur to open the LGIC vault? Or is loop-C the lock at all?

For decades, some research groups proposed that loop-C was the mechanical link, but there were no conclusive data supporting that claim. Nor was there a way to determine loop-C’s role in the opening of the channel. Indeed, large molecular perturbations to this loop — such as full deletions — also prevent ligand binding. Ligand binding and channel opening are “inextricably entwined,” Cymes and Grosman wrote.

Ligand-gated ion channels of the Cys-loop-receptor type were long thought to be only present in animals. That is until the late Eric Jakobsson, a professor of molecular and integrative physiology, discovered them in bacteria and archaea.

“Some of these bacterial counterparts turned out not to require the binding of small-molecule ligands to open,” Grosman said. “Instead, some bacterial members of this group of receptors open upon binding protons, H+, elsewhere in the extracellular domain, without involving the capping of loop-C.”

They had found a workaround. Cymes and Grosman would replace the loop-C containing extracellular domain of animal Cys-loop receptors with that of a proton-activated receptor from bacteria and attach it to the membrane-embedded pore of an animal LGIC. “We were bringing two parts together: one part from one protein, one part from another protein — a chimera,” Grosman said. Loop C could now be deleted without compromising the binding of activating protons. They had found a way to disentangle ligand binding and channel opening.

The chimera allowed for a simple process of elimination. If the loop-C-deleted chimeric channel remained closed after binding protons, then loop-C — the only missing variable — had to be the mechanical link. If the channel opened up anyway, then science’s understanding of synaptic transmission was incomplete.

“When we used protons, we asked, ‘Does the channel still open?’ The answer is yes. The chain worked,” Grosman said. “That suggested that loop-C is not required to open the port.”

They were surprised; the idea of loop-C capping initiating a domino-like cascade of events culminating in pore opening was intuitive and appealing.

“Our results suggest that the communication between the (extracellular) ligand-binding and (transmembrane) domains hinges on very subtle structural rearrangements that have, thus far, eluded identification,” Cymes said.

It remains unclear how the extracellular and transmembrane domains of this superfamily of receptors are functionally coupled to each other.

“It is precisely this coupling of ligand-binding and effector domains that underlies the physiological role of all receptor ion channels as transducers of extracellular chemical signals into the cell. Having now ruled out the involvement of loop-C capping in this process, we are closer to an answer,” Cymes said.

Their discovery could hold real implications, from developing safer neuroactive compounds to attaining a better understanding of how naturally occurring mutations cause congenital diseases.

The Grosman lab continues its efforts to elucidate the structural basis of domain–domain communication in multi-domain proteins using patch-clamp electrophysiology, quantitative ligand-binding assays, and cryogenic electron microscopy.

“This is a widespread phenomenon that underlies the transduction of signals between the extracellular milieu and the interior of a cell in all living systems,” Cymes said.

Added Grosman, “Complex human experiences and disorders are fundamentally manifestations of molecular-level events. By investigating the specific roles of amino acids and proteins, we can better decode the biological basis of emotion, addiction, and disease.”