Biochemistry Student Quinn Peterson has been awarded a 2009-2010 American Chemical Society Predoctoral Fellowship. He is working on a cancer treatment, and doing clinical tests on dogs.

Quinn Peterson does not have a dog, but he is becoming one of dogs’ best friends.

Peterson, an analytical chemist by training and a fourth-year graduate student in the Department of Biochemistry, working in Paul Hergenrother’s lab, is developing a drug to fight cancer by using it to help afflicted dogs.

Quinn has been awarded a 2009-2010 American Chemical Society Predoctoral Fellowship, which is sponsored by the ACS Division of Medicinal Chemistry. Nine graduate students were selected to receive the award, consisting of a $24,000 stipend.

“The study of cancer, and looking for different mechanisms and targets for treating cancer, is fascinating,” Peterson says.

Peterson is focusing on a compound, PAC-1, that re-activates cell-killing properties of a protein, procaspase-3. Researchers know that the procaspase-3 protein is important in apoptosis. For some reason, even though procaspase-3 is up-regulated in many cancers, it does not kill cells in that setting.

A few years ago Hergenrother’s lab screened many compounds and found one, PAC-1, that increases the activity of procaspase-3. In mouse models, Hergenrother’s lab established that PAC-1 retarded the growth of the tumor by re-activating the moribund procaspase-3 protein. And, because procaspase-3 was up-regulated in cancer cells, those cells are more sensitive to the PAC-1 effects than healthy cells.

“So this looked like a good compound to pursue through drug discovery,” says Peterson.

Peterson, who arrived on campus in 2006, was part of the team that determined how PAC-1 works. He helped establish that zinc was inhibiting procaspase-3 from working and that PAC-1 was a zinc chelator. By chelating zinc, PAC-1 stops zinc from blocking the activity of procaspase-3 and thus enables procaspase-3 to kill cancer cells.

But what of the dogs? Because Peterson is particularly interested in developing a new chemotherapy drug, he wanted to test the safety and efficacy of PAC-1 on dogs with lymphoma. In addition to understanding how PAC-1 works, he’d like to determine PAC-1’s toxicity and how it is metabolized, which will determine the best dosing procedure and the overall therapeutic strategy.

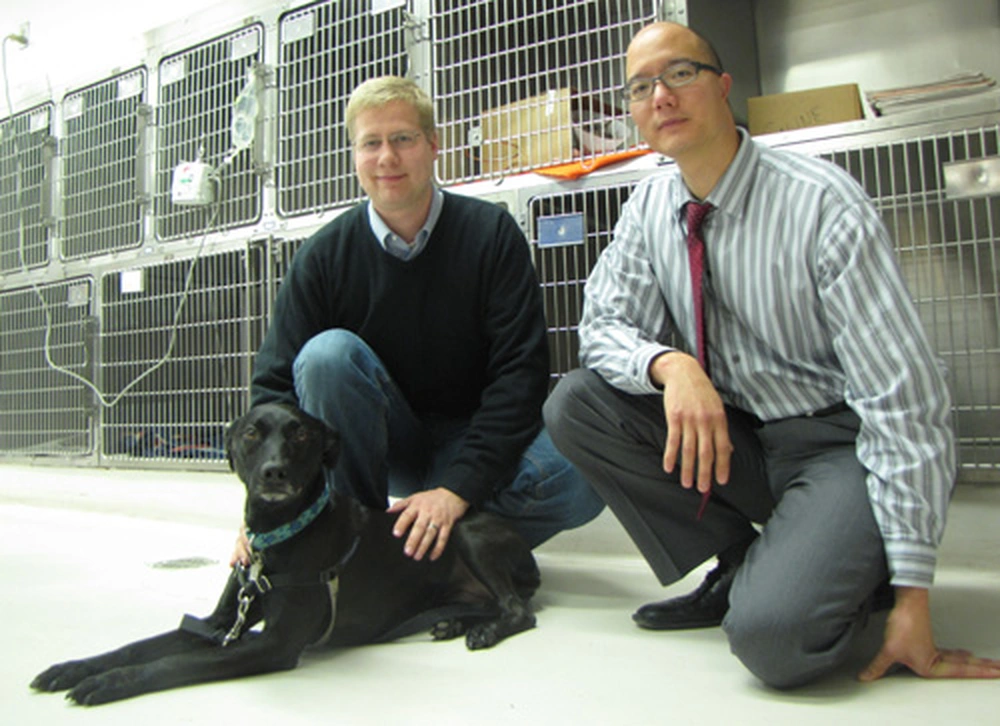

And so the dog clinical trial was begun at the School of Veterinary Medicine in collaboration with Tim Fan at the Vet School and other graduate students in the Hergenrother lab. Local owners of dogs suffering from cancer were given an opportunity to volunteer their dogs for treatment, in exchange for not only the new procedure but conventional chemotherapy.

In an early stage, using healthy, adult hound dogs to study how fast PAC-1 was metabolized, the researchers realized that the compound was getting into the central nervous system, where it was causing seizures. Peterson was able to re-design the compound so it could no longer permeate the central nervous system.

“It’s incredibly safe,” he says of the re-designed compound, “it has very few side effects in dogs, which is not always the case in terms of conventional therapies.”

The clinical trial is in a very early stage — only six dogs have been enrolled — but Peterson is cautiously optimistic about the preliminary findings.

“We’ve been able to see a significance decrease in the growth of the cancer,” Peterson says. “Dogs with untreated lymphoma would survive only between four and six weeks. But after the four-week PAC-1 treatment, while there is not remission, there is no further tumor growth.

“Ultimately we’re really hoping to find a PAC-1 derivative that is more stable and could be administered as a shot and have a longer lasting effect,” Peterson adds.

By seeking dogs through other veterinary schools, Peterson hopes eventually to have 40 dogs in the trial and to get enough data to warrant human trials.

“It would be very satisfying to anyone to see a strategy they helped develop to cure cancer was being used,” says Peterson.