The phone call came out of the blue.

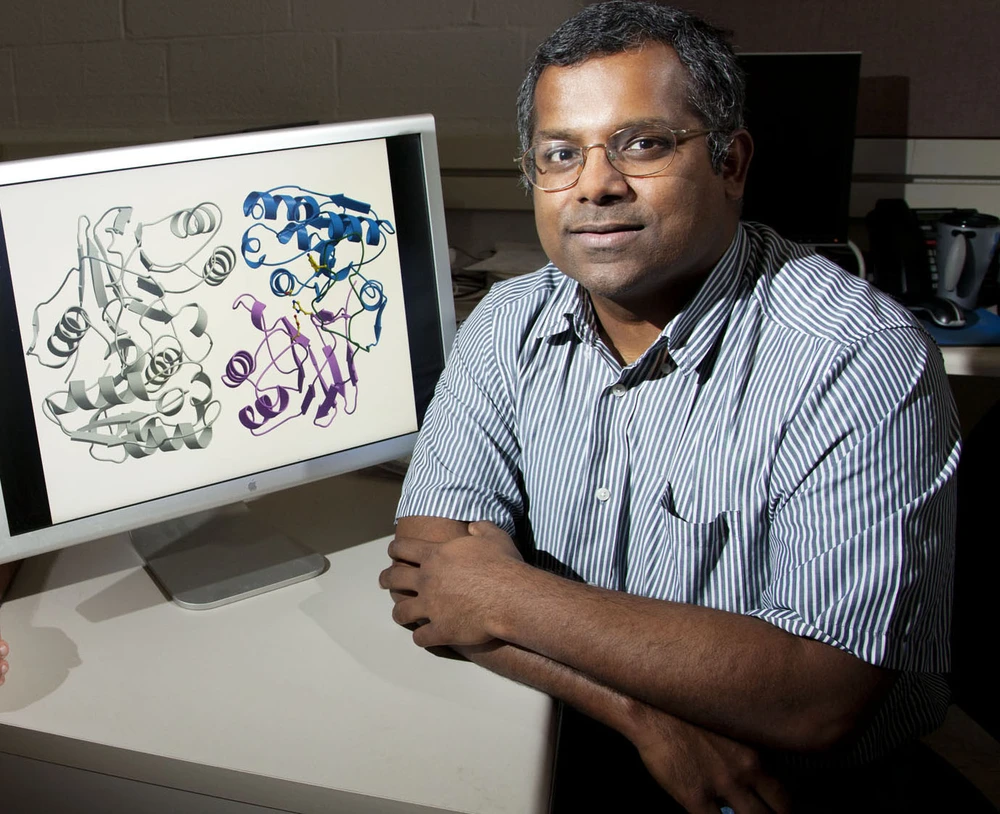

Over a year ago, Satish Nair, director of the Center for Biophysics and Quantitative Biology, received a call from Arthur DeVries, retired professor of animal biology. DeVries is well known for discovering “antifreeze proteins” in Antarctic fish, and he wondered if Nair was interested in working with him to delve deeper into the protein’s unique qualities.

The antifreeze protein prevents fish in the Antarctic from freezing, but researchers didn’t fully know how it worked, Nair says. So he joined the effort, and over the past year they have learned that this prism-like protein allows water molecules to bind to its sides, disrupting the formation of ice lattices in the fish’s blood.

This collaboration is a typical example of the kind of multidisciplinary efforts that pop up routinely in the University of Illinois Center for Biophysics and Quantitative Biology, says Nair, who became director in the summer of 2016 after serving as interim director for a year.

Collaboration is built into the center’s DNA.

“On any given day, someone might knock on your door and say, ‘Do you have a few minutes? Let’s talk a little bit about science,’” Nair says. “That might spin off into something that becomes a long-term project.”

The Center for Biophysics and Quantitative Biology was established in 1996 and has always made its home in the School of Molecular and Cellular Biology. The original idea of the center was proposed back in 1978 when Antony Crofts was recruited from the University of Bristol and appointed to lead the biophysics division in the Department of Physiology.

The Center became a formal manifestation of a “super highway” that already existed between the departments of physics and the biological sciences in MCB through Professors Gunsalus, Hager and Weber in Biochemistry and Professors Frauenfelder, Debrunner and Munck in Physics. Graduate students began to flow freely between the both sides of Green Street, which separates the Colleges of Engineering and Liberal Arts/Sciences. The current Director of MCB, Professor Stephen Sligar, is a Ph.D. physicist who graduated from the University of Illinois in 1975 and has held positions in the Department of Biochemistry, Department of Chemistry, and the Center for Biophysics and Computational Biology.

Over the course of the next two decades, as interest in biophysical areas continued to expand on campus, multiple proposals for establishing an independent center were put forth. And after several years of negotiations, the present structure of the center became reality under Colin Wraight's leadership.

The biological revolution of the 1990s, with the major strides in gene sequencing, also helped to spur the creation of this new center.

“The artificial barriers that people put up between fields started to disappear at that time,” Nair says. “You had a lot of professors trained in classical physics wanting to move into biology, and you had biologists wanting to expand their research into other disciplines as well.”

Although the center was not approved by the Board of Trustees until 1996, its roots stretch back to shortly after World War II, when the U of I beefed up the life sciences by creating the Photosynthesis Lab. This lab’s research was known worldwide, and at the heart of the work was biophysics, Nair says. The Photosynthesis Lab led directly to the creation of a biophysics program at Illinois, which is one of the pillars of the Center for Biophysics and Quantitative Biology.

"It has been very exciting to watch biophysics grow from a program to a thriving center," says Cindy Dodds, administrative coordinator of biophysics. "When I began in 1994, we had a core faculty who were primarily studying photosynthesis and electrophysiology. Now our faculty study everything from single molecules to theoretical modeling."

Over the years, the center has become a well-traveled bridge between engineering and life sciences. It draws on the expertise of over 40 affiliate faculty members from a variety of departments, including biochemistry, physics, chemistry, chemical engineering, molecular and integrative physiology, cell and developmental biology, computer engineering, bioengineering, microbiology, and more.

“I have had many wonderful students from biophysics over the years, who have driven my research in new directions,” says Martin Gruebele, head of Department of Chemistry and James R. Eiszner Chair. “My earliest biophysics student, Wei Yang, showed how proteins can fold ‘downhill.’ He is now a faculty member at the Academia Sinica in Taiwan.”

In addition, the center has played an important role in supporting the Center for the Physics of the Living Cell (CPLC), a NSF-supported Physics Frontier Center that emphasizes quantitative aspects of single molecules. For instance, physics professors Taekjip Ha and Oleksii Aksimentiev, along with bioengineering professor Jun Song, are studying how single-molecule bending of DNA affects things like genome regulation.

“It’s amazing that you can combine disparate experimental, theoretical, and computational areas of expertise, and go all the way from single molecules to whole genomes,” says Paul Selvin, a member of the CPLC.

According to Nair, the Center for Biophysics and Quantitative Biology aims to play a big role in the U of I’s new medical college, which will also unite engineering and life sciences. As he puts it, the center’s collaborative spirit “gives us a strength that is unassailable.”

As an example of this unassailable strength, he cites the work being done on blood clotting by Chad Rienstra in chemistry and Jim Morrissey and Emad Tajkhorshid in MCB. Morrissey’s lab synthesizes a phospholipid known as PS, while Rienstra’s lab analyzes the lipid’s 3D structure using new approaches to nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Then Tajkhorshid’s lab runs computer simulations of the interaction between lipids and membrane proteins—a key interaction in the blood-clotting process.

“If you have three people who are world experts and they’re all focusing on the same thing, and they’re on the same campus, that is ideal,” Nair says.

The center was originally known as the Center for Biophysics and Computational Biology, but Nair says that “Quantitative” was officially added to the name in 2015 as a way to expand its scope to include research in computational genomics, synthetic and systems biology, and quantitative proteomics.

“It is our hope that the new name will attract faculty who do not normally consider themselves biophysicists, but whose research would be perfectly synchronous with those of our other faculty,” he says.

The center is a degree-granting program, with the current contingent of PhD students totaling 45. Sixteen of them are in labs of faculty with a primary appointment in MCB, 13 are in physics labs, 8 in engineering, 7 in chemistry, and 1 in math. According to Nair, the center attracts top-quality PhD students with a unique and broad range of skills.

“It’s typical for us to get a student who might be a double major in astrophysics and biology,” he points out. “This kind of student usually wouldn’t apply to either physics or biology because they’re interested in doing both.”

More than 50 percent of the graduates go on to post-doctoral studies at top universities in the world, such as Harvard, MIT, Berkeley, and Stanford. Roughly 20 percent go into either industrial positions at places like Dow or Indigo, or software and hardware development at such companies as Intel, Advanced Micro Devices, and Lab7. Of the remaining students, about 15 percent go directly into academic positions or complete their medical degrees.

All PhD students in the center are required to do two eight-week-long tutorials, and Nair says they are encouraged to do their tutorials with faculty completely outside of their specialty area. For instance, students well versed in computational biology might want to learn more about experimental methods, so their tutorial could take them into a lab setting.

This is just another way to get students out of their comfort zone and into a collaborative frame of mind. Nair says he saw this spirit from the very beginning of his time at U of I.

“When I was going through my interviews for the job at Illinois, there were people who already wanted to collaborate with me, even before I received the formal job offer,” he says.

This multidisciplinary emphasis brought Nair to Illinois in 2001, and it is also the reason he joined the center immediately after arriving here.

As he explains, “I knew that if I came to a campus where other people were interested in working with me, I would certainly be much more successful than if I went to a campus where I was on my own.”