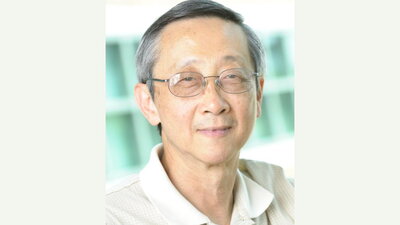

Albert Feng, a passionate and beloved scholar who studied the neural basis of sound communication, has passed away.

A virtual memorial service will be held Sept. 18. His obituary may be viewed here. A video featuring a 2011 interview with Professor Feng talking about his research may be viewed here.

Using frog and bat auditory systems as models, Feng’s research into the mechanics of hearing helped him and his colleagues at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology to design an intelligent hearing aid that boosts sound signals of interest embedded in other sounds in the immediate environment of the listener.

“Al was an extraordinary mentor,” said Daniel Llano, a professor of molecular and integrative physiology in the School of Molecular & Cellular Biology and the Beckman Institute. Llano is a PhD graduate of Illinois who explores the mechanisms by which complex sounds, such as speech, are processed by the auditory system. He was advised by Feng.

“First, his knowledge base was amazing. In lab meetings, he would regale us with stories about seemingly arcane animal behaviors, and the next moment do a deep dive into neural network theory, and then somehow in the end tie everything together. He also had the courage to do one of the most difficult things that a [principal investigator] has to do—he gave us the freedom to work on problems that interested us. And finally, Al was a caring human being. For example, our first child was born when I was still a member of the lab, and Al put the birth announcement up in the lab ‘wall of fame.’ Through these qualities, Al created a wonderful environment that shaped my development, and the development of many other scientists,” Llano said.

Professor Feng’s influence on auditory physiology continues to be felt today. Early in his career, he was the first researcher to discover that “combination” neurons exist in the brain, according to Llano. These neurons, which respond to combinations of sounds, but not individual sounds, are critical to how our auditory system processes complex sounds. That seminal discovery launched decades of research by dozens of research groups to understand mechanisms of how these neurons develop such specific response properties, Llano said.

“Toward the end of his career, Al helped to discover a novel group of frogs that are sensitive to ultrasound, which completely changed the way that we conceive of how the brain localizes sounds. In fact, Al was still actively involved in field research on these frogs over the past few years. The key that tied these lines of research together is that Al always was a keen observer of animals’ natural behaviors and used these behaviors to guide his experiments in the auditory system,” he said.

Albert Feng received a BS in electrical engineering and an MSc in biomedical engineering from the University of Miami. For his graduate education, he combined his interests in biology and engineering at Cornell University, pursuing a PhD in neurobiology and behavior and electrical engineering. After conducting postdoctoral research at the University of California San Diego, and Washington University, he joined the University of Illinois faculty in 1977.

Frogs and bats communicate by sounds in acoustically complex environments. Male frogs produce advertisement calls in large choruses, and females must localize and identify the callers based on the spectro-temporal characteristics of males’ vocalizations. Feng’s research explored the mechanisms underlying extraction of signals in complex auditory scenes. Echolocating bats rely on analysis of echoes of their sonar emissions to determine the location and identity of objects along their flight paths and to discriminate prey from obstacles, as well as stationary from moving objects.

At the U of I, he was a professor of molecular and integrative physiology, biophysics and computational biology, neuroscience, and bioengineering. He served as head of the Department of Molecular & Integrative Physiology from 1992 to 1997, and he held the title of Richard and Margaret Romano Professorial Scholar. He also previously served as associate director of the Beckman Institute and chair of the Neuroscience Program.

“Al was not only a great scientist and highly respected leader in auditory physiology, but he also did a great job in recruiting new faculty to the department,” said Benita Katzenellenbogen, Swanlund Professor of Molecular and Integrative Physiology and Cell and Developmental Biology. “He had a most wonderful and warm personality and a great smile. It was always a pleasure to interact with him,” she added.

“Over the nearly 40 years I knew Al Feng, what always drew my attention was the expressiveness of his face and body language,” said Martha Gillette, Alumni Professor of Cell and Developmental Biology and director of the U of I’s Neuroscience Program. “When in repose, he radiated focused thoughtfulness. But, he loved a social setting,” she said, whether that was presenting lectures to wide-eyed graduates, besting a colleague at a friendly game of tennis, or debating about how to best extract an informational auditory signal from the white noise of sounds beneath a waterfall. “Al had a smile on his face like the sun coming over the mountains,” she said.

“Al had a vision of greatness--for himself, for his family, for his students, for the Department of Molecular & Integrative Physiology, for the Neuroscience Program, and for the University of Illinois. He enhanced lives at each of these levels and made an indelible imprint,” Martha Gillette said.

When Feng joined the Department of Physiology & Biophysics (now Molecular & Integrative Physiology), the areas of comparative and adaptational physiology were at their height, led by the eminent dean of those areas himself, Ladd Prosser, said Rhanor Gillette, emeritus professor of molecular and integrative physiology. “Al was already well trained in those areas for his interests in animal social communication and its physiology. In marrying his laboratory studies with incisive observations and markedly imaginative experiments on bats and frogs in the field, he forged a widely recognized reputation for ingenuity and rigor,” he said.

That led to Feng’s elections as a Fellow of the Acoustical Society of America in 1997, as a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1995, and as a Fellow of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation in 1988. His scientific accomplishments and recognition also led to his popular election as president of the International Society of Neuroethology.

“Thinking about Al and his smile reminds me about the broad trajectory of his interesting life. Travel from Indonesia, to Miami, to San Diego, to Champaign-Urbana, to Munich, to China, to the many world-wide destinations across the arc of his life. I have no doubt that his smile contributed to the way he effortlessly bridged with these new environments and made friends,” Martha Gillette added.

Read more about Professor Al Feng's research:

--The little frogs with the big sounds

--Female concave-eared frogs draw mates with ultrasonic calls