Dr. Sayeepriyadarshini “Sayee” Anakk is newly promoted professor of molecular and integrative physiology whose research program focuses on understanding liver metabolism in normal and diseased states. MIP graduate student Haichao Wang spoke with her for a feature in the 2024 Molecular & Integrative Physiology newsletter.

How did you first get interested in science, and what excites you most about working in academia?

I always wanted to do something different, be a non-conformist, but I did love science. My first hands-on research laboratory experiment in my second year as an undergraduate student made me realize how much I enjoyed bench work. Whether it was collecting soil from the desert, isolating microbes, streaking plates or designing and prepping for experiments, I wanted to be in this environment for the long haul.

For me, I romanticize scientists as detectives (the 007s) and it keeps academia exciting with a constant pursuit of answers. Every experiment is a mystery waiting to be solved. Even though the reality of science is that most hypotheses fail, each failure leads us closer to understanding the bigger picture. It’s the process of figuring out why something didn’t work as expected—learning from every misstep—the thrill of uncovering small but meaningful insights fuels me every day.

As someone who has recently achieved the title of full professor, what has been your biggest takeaway from your academic journey so far?

Passion has been my guiding force. In academia, the road is competitive and demanding. But I found that balancing your goals with persistence helps navigate the setbacks and challenges that come along.

I am thankful to various mentors and colleagues who inspired me along the way. As I was beginning my independent laboratory, one piece of advice I got was to “keep your passion and perseverance even when you feel like you are ‘falling down a cliff.’” That advice has resonated with me, especially during challenging times. I also learned that pursuing research with integrity, patience, and a sense of purpose is essential. Academia requires both grit and flexibility, but if you’re truly passionate, you’ll find your way.

What are some of the most significant changes you've noticed in your field over the past decade, and how has your research adapted to these developments?

The advancements in technology over the last decade have been transformative. Over the last few decades, our understanding of the liver and bile acid biology has come a long way. The liver performs hundreds of functions, but how is it able to handle all these functions, prioritize them, and maintain regenerative response? We focus on how bile acids (a cholesterol metabolite) synthesized in the liver may be mediating some of these processes.

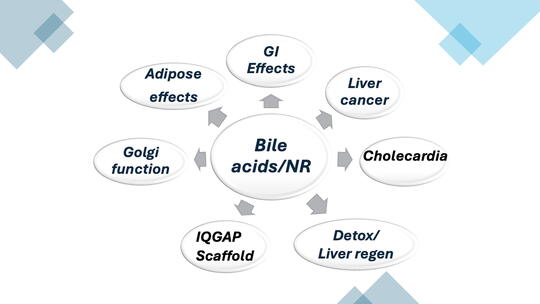

When I started, we mainly approached these questions through genetics and looked for broad patterns. Now, with technologies like mass spectrometry and high-throughput screening, we can pinpoint specific bile acids and other metabolites in very small quantities across various tissues. In fact, bile acids, traditionally considered as detergents, are now well accepted as molecular signals that actually function as hormones. Some of our work and others in the field have expanded their signaling roles into various other tissues like fat, the nervous system, and the heart.

Cutting-edge mass spec technology has led to identification of hundreds of bile acids with different side chains including a variety of amino acids. The potential that these modifications change their chemistry and signaling is mind boggling. We are at the tip of the iceberg for uncovering bile acid mediated physiology. Studies from ours and others have shown that bile acids could have functions beyond metabolism, including roles in immune response and gut health. We have been fortunate to collaborate with scientists from diverse fields, using advanced tools to explore bile acids’ influence on the microbiome, immunity, and other metabolic pathways. As a physiologist, it is thrilling because we’re moving from viewing organs as isolated systems to understanding the body as a network of systems constantly in dialogue.

Liver diseases and metabolic disorders are increasingly common globally. Do you have thoughts on how your research might impact public health approaches or awareness around these issues?

Yes, improving public health is always the ultimate aim. We began studying bile acids out of scientific curiosity, and because many liver diseases increase the circulating levels of bile acids. We found that bile acids encapsulated in nanoparticles can reduce adipocyte size, but high bile acid levels are detrimental for heart health. Moreover, we have demonstrated that bile acid composition is crucial, and overload can affect metabolic health and facilitate liver cancer. This opens the door to using bile acid profiles as diagnostic tools while decreasing their levels could be therapeutic for liver cancer.

A “eureka moment” in our research was an unexpected finding that increases in bile acids may prime the detoxification pathways in the liver and can be protective against hepatotoxic drugs. When we challenged a genetic mouse model with elevated bile acids with toxic dose of Tylenol, we discovered that they are resistant to liver toxicity from common drugs like Tylenol. Additionally, we find that one of the detoxifying proteins, CYP2B6 in biliary atresia patients (children with high bile acids), was highly expressed, which was similar to our mouse studies and thus rewarding to see the potential clinical impact. Another one (Eureka 1.1, haha) was when we realized that bile acid homeostasis and their signaling is sex-specific not only at the liver but also in the gut, wherein bile acids interact with the microbiota. We find that the bi-directional crosstalk between bile acids and microbiota shape gut health, various disease pathology and overall metabolism. So, one of the goals is to test if manipulating bile acid profiles to promote a beneficial gut microbiome or vice versa, in turn, improve overall health. We hope this research will eventually help provide personalized interventions based on an individual’s unique bile acid and microbiome profile.

For students and young scientists interested in life sciences or your field, what resources or areas of study would you recommend they focus on to prepare for a career in these fields?

My advice is to cultivate a true passion for the topic of your research because that will sustain you through the inevitable highs and lows. Beyond learning techniques, young scientists need to understand the context behind them. I often see students focused solely on the latest high-profile papers, but science is cumulative, and knowing the foundational work is essential.

Another piece of advice I got was to spend at least 50% of my time thinking critically about an experiment before diving in. That advice has stayed with me because reflection and planning are just as important as execution. Nowadays, too much data is generated, young scientists should be trained to dig in and focus on interpretation, take time analyzing it, think deeply about the results, what they imply and understanding its limitations.

Apart from your research, what do you enjoy?

Outside of the lab, I’m something of an adrenaline enthusiast! Maybe that’s why the love for hormones! I do enjoy hiking, traveling, riding a motorcycle and want to try bungee jumping one day. Connecting with nature brings a sense of balance that I find refreshing after long hours in the lab.

If you had to choose a different field of research other than your topic, what would it be?

Honestly, I’m not sure—I just love the liver. But if I hadn’t stayed in research, I might have become a high school science teacher or a dance teacher. I’ve trained in traditional Indian dance for more than a decade, so I could see myself going down that path