Ask any scientist and they’ll tell you what a joy it is to discover something they didn’t know they didn’t know. “The best parts of science tend to be serendipitous,” said the School of Molecular & Cellular Biology’s Jhewelle Fitz-Henley. “The things that you find out, you’re like, ‘I did not think that was going to happen.’”

However, for many new college students, figuring out how to balance classes, find a lab, and pay for school is hardly one of “the best parts of science.”

That’s why, after nearly three years in development, the School of MCB CREW Program launched this fall. Now in its pilot year, CREW recruits a cohort of Federal Work-study-eligible undergraduates, pays them to conduct lab research, enhances their presentation skills, and teaches them everything they didn’t know they didn’t know.

“Undergrad research is kind of a black box,” said Dr. Fitz-Henley, who is the School of MCB’s Assistant Director of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Outreach as well as one of CREW’s Co-Directors. “The whole program is geared towards teaching the hidden curricula behind being a successful undergrad researcher — it’s all about equipping students with more tools for success.”

What became CREW was the brainchild of a former University of Illinois professor who recognized a concerning pattern — a dearth of students who had to work to support themselves in college among those conducting independent research in MCB laboratories.

Since few CREW-like initiatives exist nationwide, Fitz-Henley and Cell & Developmental Biology professor Rachel Smith-Bolton had to start from scratch designing the program.

“Programs like this are very unusual across institutions,” Dr. Smith-Bolton said. “One of our goals was to facilitate access for people who wouldn’t necessarily be equipped to put themselves out there and find a lab space with everything else they’re doing. We figured that once students are introduced to that hidden curriculum, then the science will follow.”

Fitz-Henley and Smith-Bolton centered the program around a course which, instead of teaching scientific concepts, prioritizes skills that largely go untaught in the classroom.

“We talk a lot about time management in class,” Fitz-Henley said. “We talk about scientific literacy because no matter what lab you’re in, you’ll be reading scientific papers. We also expect them to discuss their science in public: how to properly communicate hypotheses, results, their significance, and how to put that all on a slide.”

“I never had any research experience before,” said Haylee Barnard, a sophomore majoring in Molecular and Cellular Biology and one of CREW’s five students. “There’s a big learning curve because there’s a lot of techniques to learn, especially depending on which lab you’re in.”

Barnard spent her first year at Illinois as a biochemistry major but, after applying to and getting accepted into CREW, made the switch to the Molecular and Cellular Biology major. Her work in a microbiology lab played a pivotal role in that decision, all while granting her a little more financial flexibility, she said.

CREW has also given Barnard a community of people with similar experiences. “All five of us started from square one,” she said. “None of us had any research experience. We all had imposter syndrome and thought ‘Everyone else knows what they’re doing, but I don’t.’ Talking about that openly with others has been really helpful.”

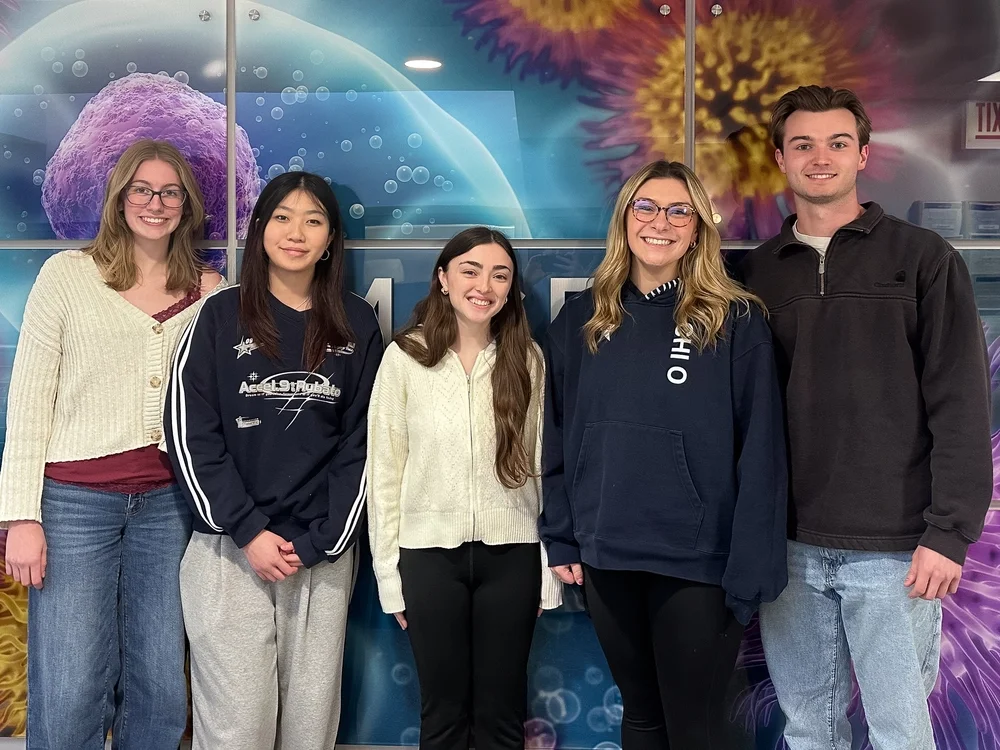

Barnard and her four fellow CREW members don’t just discuss their ideas in class — they gave their first research presentations in early December 2025. By the time she graduates in 2028, she will have given six.

Fitz-Henley and Smith-Bolton said the CREW students impressed at that initial symposium. Research topics ranged from viral density in the Yellowstone Hot Springs — Barnard’s research — to muscle regeneration, to liver disease.

Even though each CREW cohort is small, Fitz-Henley says its benefits are reverberating throughout the entire MCB community.

“The faculty are really enjoying mentoring these students,” Fitz-Henley said. “We’re initiating conversations between undergraduates about research, giving mentorship experience to postdocs and grad students, all while paying the students without using lab budgets.”

Because of the program’s early successes, CREW could set the example for more to follow.

“The CREW program could be a fantastic model for how to do undergraduate research in general,” Smith-Bolton said. “This framework and structure could be implemented not just with a targeted group, but, maybe one day, across the entire undergraduate population for students in labs.”