Researchers from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign are piecing together how cancer-emergent non-coding RNAs, or ncRNAs, contribute to disease-related cell phenotypes. The Van Bortle lab has focused extensively on RNA polymerase III (Pol III) — an enzyme that produces RNA molecules — and has recently directed its attention to understanding the functions of ncRNAs specifically produced by Pol III.

Their findings appear in the journal Nature Communications.

Non-coding RNAs are RNA molecules that do not encode proteins (the product of other RNAs called messenger RNAs, or mRNAs) but instead have important functions such as organizing and regulating specific processes inside a cell. Members of the Van Bortle lab in the Department of Cell & Developmental Biology of the School of Molecular & Cellular Biology wanted to look at a specific class of Pol III-transcribed ncRNA, snaR-A, which is highly expressed in cancer cells, to uncover its biological function.

“We know little-to-nothing about the function of this non-coding RNA, aside from the fact that it’s produced by Pol III in several cancer contexts” said Sihang Zhou, a graduate student in the Van Bortle lab and lead author of the paper. “Conversely, we know quite a lot about other Pol III products, like tRNA, rRNA and other categories but have learned very little about snaR-A since its discovery nearly twenty years ago.”

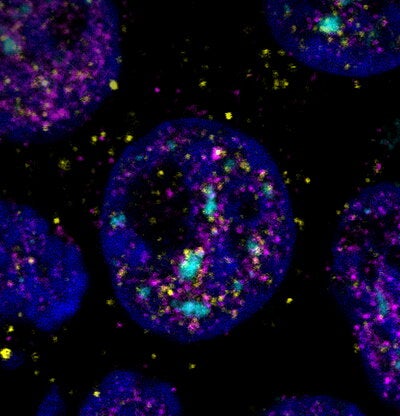

Using biochemical and genomic techniques, the Van Bortle lab has now discovered that snaR-A disrupts mRNA splicing — a process meant to produce mature mRNAs for translation — and that disruption has downstream consequences associated with pro-growth genes. In addition to discovering snaR-A at subcellular bodies associated with splicing, Zhou noticed that there was a decrease in intron retention levels after reducing snaR-A levels and the opposite result following overexpression of snaR-A.

“There seems to be crosstalk between it (snaR-A) and splicing — another hotspot in cancer, as lots of cancer mutations converge on the same splicing machinery that snaR-A disrupts” said Kevin Van Bortle, assistant professor of cell and developmental biology.

Van Bortle and Zhou originally were unsure where the data would lead them. However, this observation shines new light on genetic elements derived from the “dark genome”, which refers to the large amount of repetitive DNA that is typically inactive under normal conditions and is a topic that many scientists are still trying to understand.

“The dark genome: it’s typically silenced through specific gene regulatory mechanisms that go awry in cancer, allowing for the expression of snaR-A and other ncRNAs,” Van Bortle said. This link continues to intrigue Van Bortle and Zhou as they seek to uncover the extent of Pol III expansion into other inactive repetitive elements in cancer. “As scientists, we let the data drive our hypotheses, and ultimately illuminate the biology,” he said.

Despite uncovering significant insight on snaR-A, Zhou continues to pose more questions and is determined to explore more cancer-emergent RNA species like snaR-A. Zhou’s future findings could answer more questions about the link between these ncRNAs and disease.

Photo at top: From left: Sihang Zhou, Kevin Van Bortle, Ruiying Cheng, Simon Lizarazo Chaparro, Sandip Chorghade, Rajendra KC, Auinash Kalsotra.